A New Way of Seeing

Every day, we’re surrounded by people who seem to be living in different worlds.

Some argue from “facts,” others from “feelings.”

Some focus on individual choices, others on systemic forces.

Some ask, “What’s going on inside you?” while others demand, “What’s happening out there?”

They’re all pointing at the same reality — yet talking past each other completely. It’s as if we’re each standing at a different window, describing the view, and assuming everyone else must be blind.

What if the problem isn’t that anyone is wrong — but that everyone is partial?

What if reality itself is richer, deeper, and more multidimensional than we’re used to seeing — and our disagreements are just the friction between different vantage points?

Integral theory suggests that’s exactly what’s happening. Beneath our arguments, misunderstandings, and fragmented fields of knowledge lies a simple truth: reality always shows up in four fundamental ways. These four ways are so elemental, so universal, so primordial, that they’re present in every moment of experience — from brushing your teeth to building a civilization.

Learning to see through these four lenses is like upgrading from a flat 2-D snapshot to a fully dimensional view of life. Once you notice them, you can’t unsee them. They become a compass for understanding yourself, others, and the world with far more clarity and compassion.

The Coordinates of Experience

Imagine you’re trying to map the terrain of reality. Where do you even begin?

Integral theory starts with two primordial dimensions — not inventions, but observations about how experience actually shows up:

- Interior ↔ Exterior: the inner, subjective world vs. the outer, objective world

- Individual ↔ Collective: the singular “me” vs. the shared “we”

Where these two dimensions intersect, they don’t create an abstract grid. They reveal four irreducible ways that reality discloses itself — four fundamental “locations” of being and knowing.

They are:

- The Interior of the Individual — what it feels like inside you

- The Exterior of the Individual — what others can observe about you

- The Interior of the Collective — the shared meanings and cultures we participate in

- The Exterior of the Collective — the systems and structures we inhabit

These are known as the Four Quadrants — and they are as basic to experience as north, south, east, and west are to navigation. Wherever you go, they’re already there. The question is only whether you notice them.

Let’s walk through these four perspectives in plain language, using examples you already know from your own life.

INDIVIDUAL

COLLECTIVE

INTERIOR

EXTERIOR

Upper Left: The “I” Space

(Interior Individual)

This is the subjective space of your inner world — the thoughts, feelings, intentions, memories, dreams, and awareness that only you can access.

It’s the realm of personal meaning, purpose, and first-person experience. When you say, “I feel anxious,” “I had a revelation,” or “That moved me deeply,” you’re speaking from here.

A poem lives here. So does prayer. So does the thrill of falling in love or the ache of heartbreak. It’s the part of you that notices beauty, intuits patterns, and silently talks to itself in the grocery store aisle.

Upper Right: The “It” Space

(Exterior Individua)

This is the objective view of you from the outside — your body, behaviors, physiology, and actions in the world.

It’s the realm of science and measurement: heart rates, hormone levels, neural firings, observable habits. It’s what someone else can point to and say, “Look — there.”

When a doctor measures your blood pressure, when a fitness tracker logs your steps, when someone notices you haven’t made eye contact all day — that’s the Upper-Right perspective in action.

Lower Left: The “We” Space

(Interior Collective)

This is the shared interior world we build together — culture, language, worldviews, norms, and stories. It’s the invisible fabric that makes a group feel like a group.

It’s why jokes land in one crowd, and fall flat in another. It’s why a tradition feels sacred to some and strange to others. It’s the pulse of belonging — or the sting of exclusion.

When someone says, “That’s just not how we do things here,” they’re speaking the language of the Lower-Left.

Lower Right: The “Its” Space

(Exterior Collective)

Finally, there’s the world of systems and structures — the networks, technologies, institutions, and environments that shape our lives from the outside.

Traffic patterns, economic policies, climate systems, digital platforms — these are all Lower-Right phenomena. They’re the reason your coffee costs what it does, your commute takes as long as it does, and your social media feed looks the way it does.

They’re often invisible until they break — and then they shape everything.

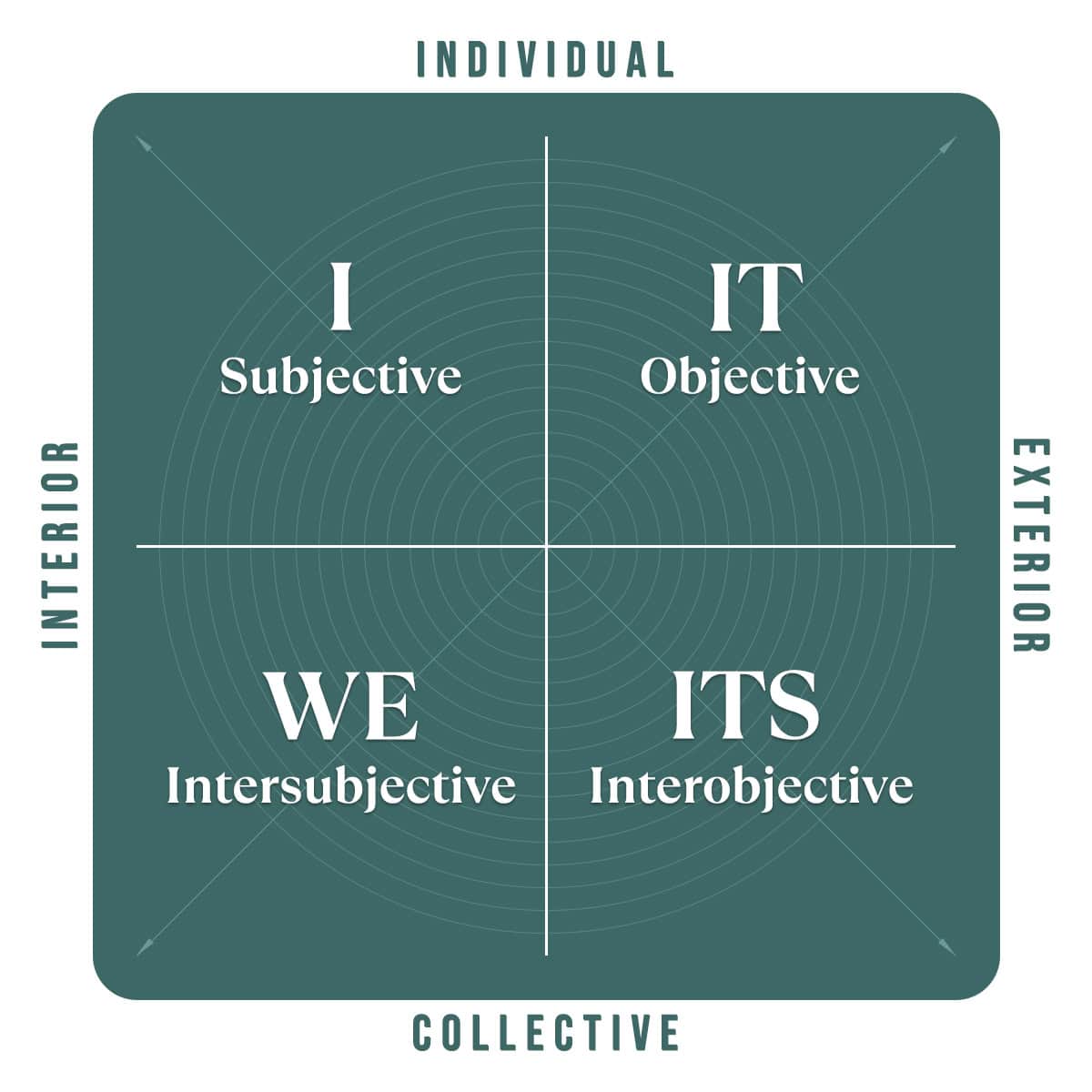

Another way to think about these four perspectives is through the pronouns we already use to describe reality.

The “I” space (Upper-Left) is subjective — the interior world of my own thoughts and feelings.

The “It” space (Upper-Right) is objective — the exterior world of things and behaviors we can measure.

The “We” space (Lower-Left) is intersubjective — the shared interior of culture, language, and meaning.

The “Its” space (Lower-Right) is interobjective — the shared exterior of systems, structures, and networks.

These four pronouns are the deep grammar of reality itself — four ways of speaking that reflect four ways of being. Every time we use “I,” “It,” “We,” or “Its,” we’re orienting ourselves within this fourfold space.

Experiencing the Four Quadrants

It’s one thing to understand these quadrants conceptually. It’s another to feel them directly. Try this short exercise:

- Upper-Left: Close your eyes. Notice what’s happening inside you — thoughts, emotions, sensations. What’s the tone of your inner world right now?

- Upper-Right: Open your awareness to your body. How are you breathing? What’s your posture? What physical signals are present?

- Lower-Left: Bring someone else to mind — a friend, a team, a community. Feel the shared space between you. What unspoken understandings live there?

- Lower-Right: Zoom out. Notice the broader systems you’re part of — your home, neighborhood, economy, digital infrastructure. What background forces shape your daily life?

All four dimensions were present just now — not as abstract ideas, but as lived realities. They are always here, always shaping your experience, whether you pay attention or not.

Why It Matters: The Cost of Partial Vision

We rarely forget that the Earth has four directions. But most of us forget that reality has four fundamental perspectives. We’re trained — by culture, education, even temperament — to privilege one or two and neglect the rest.

Some people trust only the inner world (“What matters is how I feel”).

Some trust only the outer world (“If you can’t measure it, it’s not real”).

Some focus on individuals (“People just need to make better choices”).

Others on systems (“The deck is stacked — we need structural change”).

Each is partially right. And each is dangerously incomplete.

The result? Personal blind spots. Social conflicts. Endless arguments where everyone is right — and everyone is missing something.

It’s the old parable of the blind men and the elephant. One touches the trunk and declares the elephant a snake. Another grabs a leg and swears it’s a tree. A third feels the side and insists it’s a wall. All are partially correct. None see the whole.

Our culture is like that. Scientists and mystics, activists and entrepreneurs, conservatives and progressives — all hold pieces of the truth. But we spend so much time fighting over our pieces that we rarely pause to compare notes and reconstruct the elephant.

The four quadrants don’t collapse those pieces into a single answer. They show us how the pieces fit together.

Seeing Whole: Two Ways of Looking

Learning about the quadrants is one thing. Learning to use them is another. And there are two fundamental ways to bring this map to life:

- Looking as — entering directly into another’s perspective to understand their inner world, behavior, culture, and context from the inside out.

- Looking at — stepping back and examining any phenomenon through all four quadrants to reveal a fuller picture.

Both are essential skills. And together, they transform the way we relate, lead, communicate, and solve problems.

🪞 Looking As: Speaking to the Whole Person

Most of our communication barely scratches the surface. We talk to people’s ideas but not their feelings. We critique their behavior without understanding their environment. We ignore the cultural narratives that shape their choices.

When we “look as,” we stop treating people as puzzles to be solved and start meeting them as whole beings.

Imagine you’re frustrated because a colleague — let’s call her Sarah — is resisting a new project you’re excited about. Instead of jumping to conclusions (“She’s lazy,” “She doesn’t get it”), you pause and consider the four quadrants, illustrated below.

By stepping into all four perspectives, you’re no longer reacting to a caricature. You’re responding to a complex human being embedded in a web of interior and exterior realities. That’s how trust is built. That’s how influence deepens.

🔍 Looking At: Getting the Full Story

Now flip the lens. Instead of entering a perspective, we can map it — looking at any event, phenomenon, or problem through all four quadrants.

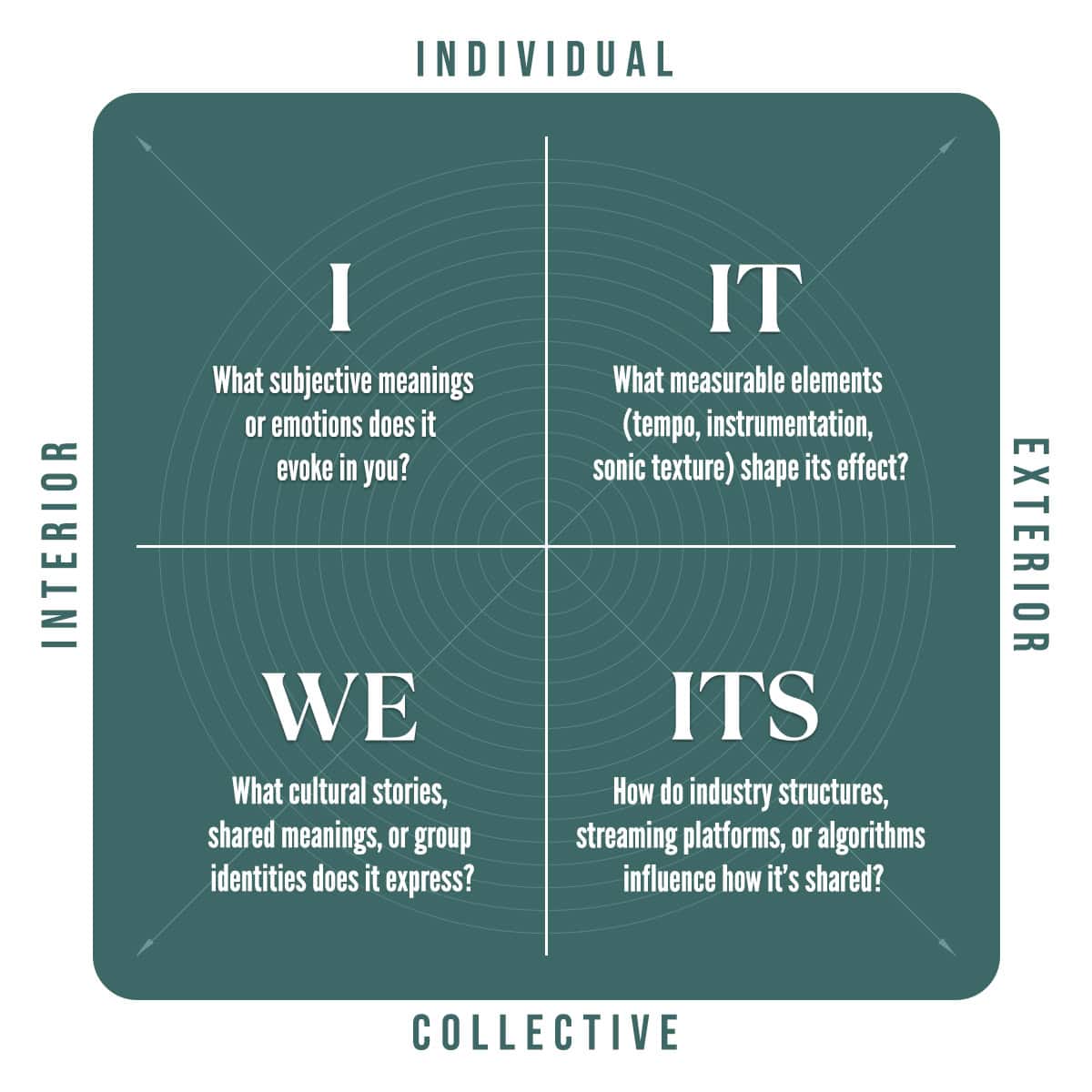

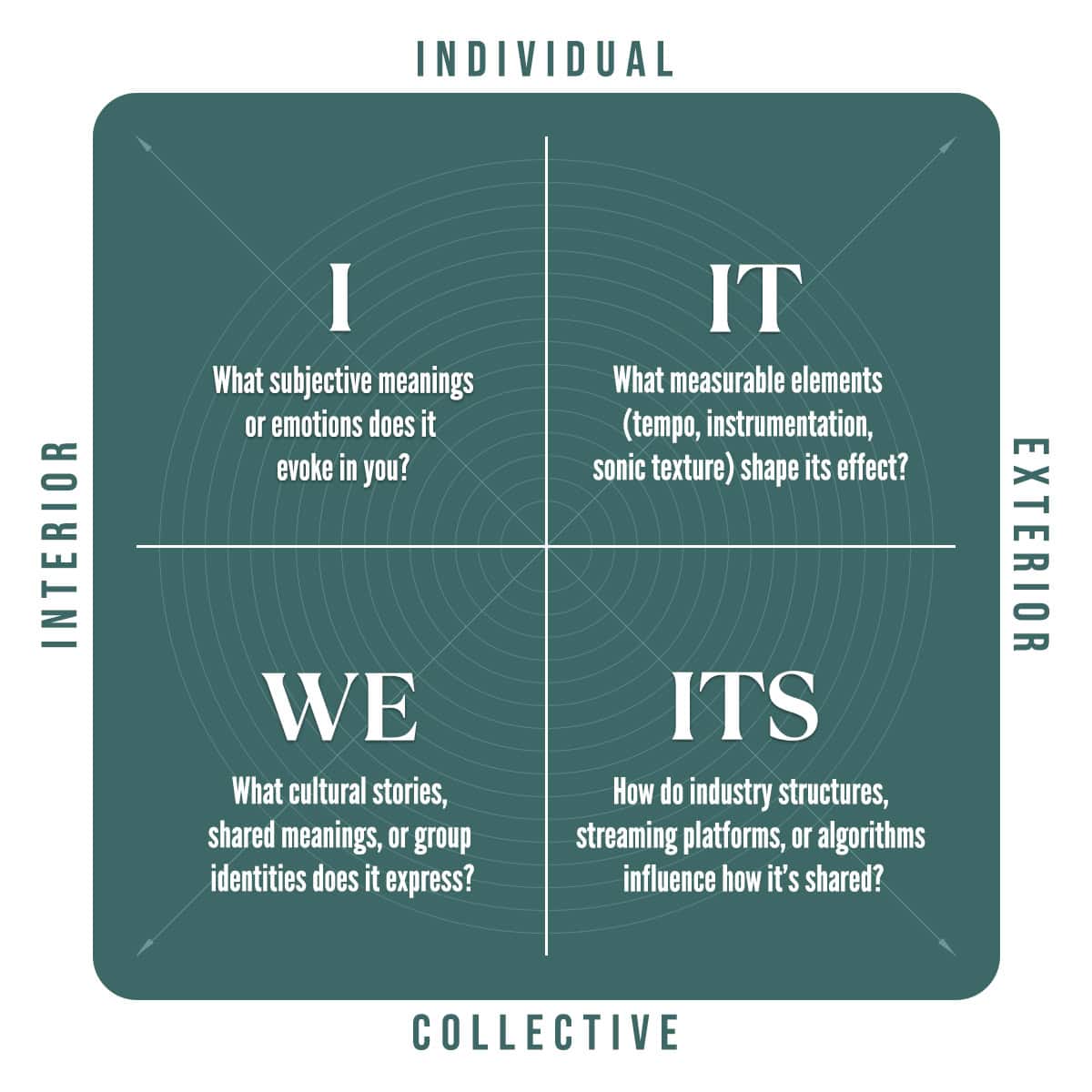

Let’s take something simple: your favorite song.

Notice how each question reveals a layer of truth. None contradict the others — they complete each other. This is what we mean by integral thinking: refusing to confuse a single perspective for the whole.

You can apply this same lens to anything — a health crisis, a policy debate, a relationship conflict, a global event. In every case, quadrant thinking turns complexity from an overwhelming mess into an intelligible pattern.

From Fragmentation to Integration

If it feels like knowledge is splintered — that’s because it is.

Science broke off from philosophy. Psychology split from sociology. Politics fractured into endless camps. Culture wars rage over which kind of truth matters most: subjective or objective, individual or systemic.

But step back, and a deeper pattern emerges: knowledge has always moved from fragmentation to integration.

Newton showed that the same laws govern falling apples and orbiting planets.

Maxwell unified electricity and magnetism into a single field.

Einstein fused space and time into spacetime — and later revealed matter and energy as two sides of the same reality.

Quantum theory reconciled particles and waves as complementary descriptions of the same phenomena.

The Standard Model integrated three fundamental forces into one framework.

Everywhere we look, deeper understanding reveals hidden unities beneath apparent differences.

The quadrants are part of that same movement — but they do it across all fields of knowledge, not just physics. They show us how mind and body, consciousness and culture, behavior and systems, all interweave into a larger whole. And they do it without flattening difference or erasing nuance.

Integration doesn’t mean everyone agreeing. It means everyone seeing how their piece fits into a bigger picture — like puzzle pieces forming a coherent image.

Everything In Its Right Place

These four perspectives are so fundamental that every mature field of knowledge eventually discovers them — even if it uses different names. But because most disciplines evolved in isolation, they tend to overemphasize one or two quadrants and ignore the rest.

Here’s how that plays out across a number of knowledge domains:

The Four Quadrants Across Multiple Fields of Knowledge

The Four Quadrants Across Multiple Fields of Knowledge

INDIVIDUAL

COLLECTIVE

INTERIOR

EXTERIOR

Phenomenological / Depth / Experiential

Focus: thoughts, feelings, identity, meaning-making

Schools: Psychoanalysis, Humanistic Psychology (e.g. Carl Rogers, Maslow), Depth Psychology, Developmental Psychology, Mindfulness-based therapies

Key concern: What’s happening in the subjective interior of the individual?

Therapy examples: Dreamwork, emotional processing, identity exploration

Behavioral / Cognitive / Neurological

Focus: behavior, cognition, neurobiology, stimulus-response

Schools: Behaviorism (e.g. Skinner), Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Neuroscience, Evolutionary Psychology

Key concern: What can we see, measure, or recondition?

Therapy examples: Exposure therapy, thought restructuring, pharmacological interventions

Cultural / Relational / Interpersonal

Focus: relational dynamics, language, values, cultural context

Schools: Narrative Therapy, Feminist Psychology, Family Systems Theory, Cultural Psychology

Key concern: How do relationships, norms, and shared stories shape psychological experience?

Therapy examples: Couples therapy, community-based work, dialogue circles

Systems / Ecological / Organizational

Focus: institutions, access, social determinants, environments

Schools: Ecopsychology, Social Justice Psychology, Organizational Psychology, Public Health approaches

Key concern: What structures and conditions support or constrain psychological well-being?

Therapy examples: Policy advocacy, systemic reform, environmental design

Why It Matters

Every psychological approach reveals part of the truth—but when one quadrant becomes dominant, others get neglected:

- Behaviorism (UR) rejected introspection (UL)

- Humanism (UL) often ignored systems (LR)

- Narrative therapy (LL) sometimes bypassed neurobiological factors (UR)

- Policy-oriented work (LR) can overlook lived inner pain (UL)

Integral psychology doesn’t ask which approach is right.

It asks: What’s missing from the picture—and how do we bring it back in?

This doesn’t dilute focus. It adds depth.

It lets us treat the whole person, within the whole world they inhabit.

INDIVIDUAL

COLLECTIVE

INTERIOR

EXTERIOR

Embodied Experience

Experience, intention, mindset, motivation This is the personal, subjective dimension of health: How do I feel? What is my relationship with my body? Do I feel empowered, ashamed, committed, overwhelmed? Healing here involves self-awareness, inner alignment, trauma work, mindset coaching, and cultivating meaning. Many wellness practices begin in this quadrant: journaling, meditation, affirmations, or addressing psychosomatic patterns.

Biological Function

Biology, behavior, symptoms, diagnostics This is the traditional domain of Western medicine. Health is defined by observable metrics: blood pressure, lab results, imaging, symptoms. It’s where we track disease, prescribe medication, perform surgery, and measure outcomes. From this view, healing is a mechanical process: diagnose the issue, fix the malfunction. The individual is treated as a physical organism.

Cultural Meaning

Cultural beliefs, identity, community norms This is the cultural meanings we assign to health: what “wellness” means within your cultural or relational context. What foods are enjoyed by the culture? What body types are idealized or stigmatized? Is illness something to be disclosed, hidden, prayed about, or scientifically explained? Healing in this quadrant includes belonging, cultural resonance, peer support, and the stories we tell about health, illness, and recovery.

Health Systems

Systems, environments, economics, policy Here, we see the infrastructure of health: food systems, insurance models, public health, transportation, access to care. Do you live near clean water and fresh food? Can you afford a doctor? Is your job high-stress or your housing unstable? Healing here means structural reform: designing systems that reduce inequality and promote access to care.

Why It Matters

All four of these dimensions shape our health. And yet, professionals and advocates often get locked into just one.

- The physician focused only on symptoms.

- The coach focused only on mindset.

- The activist focused only on systemic oppression.

- The influencer focused only on lifestyle branding.

Real health emerges when we stop asking, “Which quadrant is right?” and start asking, “What’s missing from my view?” Integrative health isn’t a trend — it’s a recognition that healing is whole.

INDIVIDUAL

COLLECTIVE

INTERIOR

EXTERIOR

Artist’s Inner World (Intention & Insight)

Artist’s intention, inner state, psychological depth This is the expressive heart of the artist: What were they feeling? What vision were they trying to convey? What unconscious forces shaped their work? Romanticism, psychoanalytic theory, and transpersonal approaches live here. Art is seen as a window into the soul of the creator—an act of personal meaning-making, self-expression, or revelation.

Formal Qualities (Technique & Structure)

Technique, form, structure, objective features of the work Here, art is treated as an observable object. What are its formal properties—line, color, meter, grammar, medium? How is it composed? This quadrant includes structuralism, formalism, and New Criticism. Meaning arises not from who made it or how it’s interpreted, but from the internal mechanics of the piece itself.

Audience & Culture (Shared Interpretation)

Shared meaning, cultural context, interpretive community This is where the audience lives—the cultural lens through which art is received and interpreted. Reader-response theory, hermeneutics, and reception theory all dwell here. Meaning is seen as co-created between artist and audience, shaped by language, worldview, and social norms. Art lives in the “we-space” of culture and tradition.

Institutions of Meaning (Distribution & Power)

Systems, institutions, economics, power structures This is the structural world around art: publishing industries, museum gatekeeping, patronage systems, algorithms, and the politics of access. Marxist, feminist, post-colonial, and critical theory perspectives emphasize this dimension. Art is seen as embedded in systems of power—always produced, circulated, and interpreted within social, historical, and material conditions.

Why It Matters

Where meaning lives in the mind, the page, the culture, and the system. Most art and literary theory schools start with one of these quadrants—and then argue as if it’s the whole.

- The formalist insists meaning lives in the structure.

- The cultural theorist says it’s all about audience context.

- The psychoanalyst dives into the artist’s unconscious.

- The Marxist critiques the systems behind the scenes.

Each perspective reveals something vital. But when one becomes totalizing, we lose the full truth of what art is—and what it does. Art doesn’t just come from a person. It isn’t just a pattern, a cultural product, or a political artifact. It’s all of those—at once. To restore art to wholeness, we need to look through all four lenses. Not just to analyze better—but to feel more, create more, and connect more deeply with the meaning at the center of it all.

INDIVIDUAL

COLLECTIVE

INTERIOR

EXTERIOR

Learner’s Inner Life (Motivation & Meaning)

Motivation, mindset, self-awareness, meaning-making This is the inner life of the learner: curiosity, confidence, fear of failure, love of learning. It includes student voice, personal growth, grit, and emotional resilience. From this lens, education is about awakening something within—supporting students in constructing meaning and discovering purpose. Humanistic, constructivist, and contemplative pedagogies often begin here.

Performance & Skill (Observable Behavior)

Behavior, performance, skills, brain function This is the measurable side of learning: test scores, cognitive development, memory, reading fluency, and observable classroom behaviors. It’s where neuroscience, instructional design, and data-driven assessment operate. From this view, education is about optimizing performance, delivering content, and measuring outcomes.

Classroom Culture (Shared Learning Context)

Classroom culture, group norms, shared values This is the “we-space” of education—the relational and cultural dynamics that shape how learning happens. It includes peer influence, inclusion, storytelling, identity formation, and school culture. From this lens, education is not just an individual pursuit—it’s something co-created in community. Culturally responsive teaching, DEI work, and restorative practices live here.

Educational Systems (Structures & Policy)

Institutions, policies, curricula, funding systems This is the structural backbone of education: school districts, national standards, bureaucratic policies, accreditation, and funding models. From this perspective, learning is shaped by the architecture of the system—access to resources, class sizes, standardized curricula, and historical inequities. Educational reformers and policymakers often begin here.

Why It Matters

Where learning happens in minds, bodies, classrooms, and systems. Education lives in all four quadrants—but most debates in education only speak from one.

- The policy expert wants better systems (LR).

- The teacher focuses on student behavior (UR).

- The mentor emphasizes inner growth (UL).

- The activist challenges cultural bias and exclusion (LL).

Each is holding a piece of the puzzle. But without the full picture, we keep cycling through reforms that treat symptoms but miss root causes. True learning isn’t just a cognitive process. It’s not just a cultural shift, a policy fix, or just a personal transformation. It’s all of these—interwoven. Quadrant-aware education means we don’t have to choose between rigor and relevance, between systems and soul. We can design learning environments that meet the full complexity of being human—and help students grow in all four dimensions at once.

INDIVIDUAL

COLLECTIVE

INTERIOR

EXTERIOR

Inner Bias & Framing (Intent & Perspective)

Intent, bias, worldview, intuition This is the inner lens of both the journalist and the consumer: What’s the reporter’s intent? What does the audience want to believe? How does this story reinforce or challenge my values? This quadrant includes ideological leanings, narrative framing, and selective attention. From this view, journalism is never neutral—every story is filtered through perception and purpose.

Facts & Footage (Observable Content)

Facts, footage, data, observable events Here, media is judged by its verifiable content: What happened? What can be confirmed? What’s on camera, in the documents, in the quote? This is the traditional domain of journalistic objectivity—accuracy, evidence, and reporting the “who, what, when, where, and how.” From this view, journalism is a mirror of events.

Cultural Framing (Shared Narrative)

Shared narratives, cultural meaning, audience identity This quadrant looks at the symbolic power of media: What story is this telling us about ourselves? Who does this narrative serve or exclude? What norms or taboos are being reinforced? From this perspective, media is a cultural artifact—something we interpret as a group, shaped by identity, tribe, and worldview. Interpretive journalism, media studies, and cultural criticism live here.

Media Infrastructure (Platforms & Algorithms)

Institutions, algorithms, platforms, monetization This is the systems-level view: What incentive structures guide the newsroom? What algorithms shape what we see? Who owns the outlet, and how is the story distributed? This quadrant explores how media is produced, filtered, amplified, and monetized—through clicks, shares, subscriptions, and censorship policies. Tech platforms, policy debates, and media economics live here.

Why It Matters

Where facts, frames, feelings, and algorithms collide. Media dysfunction is almost always quadrant dysfunction.

- One person says: “Just report the facts!” (UR)

- Another says: “This is harmful to our community.” (LL)

- A third warns: “You’re ignoring structural bias and platform algorithms.” (LR)

- A fourth claims: “You’re clearly pushing an agenda.” (UL)

They’re all reacting to different aspects of the same phenomenon. And because they don’t recognize each other’s lens, they end up dismissing each other’s concerns. Quadrant-aware media literacy doesn’t mean relativism. It means multi-perspectival clarity:

- You can care about facts and frames.

- You can call out bias and look at system design.

- You can analyze content and context.

In a world flooded with noise, what we need isn’t just “more information.” We need a more integral intelligence—a way of seeing that helps us discern what’s partial, what’s missing, and what’s needed next.

INDIVIDUAL

COLLECTIVE

INTERIOR

EXTERIOR

Inner Awareness (Self-Reflection & Identity)

Intent, awareness, identity, self-examination This is the inner work of social justice: Do I recognize my own biases? Do I understand how my identity has shaped my experience of privilege or oppression? Am I embodying my values? This quadrant includes personal awakening, allyship, anti-racism practice, and moral alignment. From this view, justice begins with inner transformation.

Action & Accountability (Behavior & Language)

Behavior, language, visible action Here, justice is measured by conduct: What did the person actually do or say? Was harm caused? Are they living out their stated commitments? This quadrant focuses on microaggressions, inclusive language, performative allyship, and visible behaviors. Accountability often plays out here. From this view, justice means walking the talk.

Collective Identity (Cultural Meaning)

Group identity, culture, shared narratives This is the “we-space” of identity: What stories shape how we see race, gender, class? What norms define belonging or exclusion? This includes cultural trauma, lived experience, language reclamation, and shifting public narratives. From this view, justice is about transforming the shared meaning systems that normalize harm or invisibility.

Systemic Conditions (Institutions & Policy)

Systems, structures, policies, access This quadrant examines the structural mechanics of injustice: policing practices, redlining, education gaps, labor exploitation, health disparities, and more. This is where activists push for legislative change, institutional reform, and redistribution of resources. From this view, justice is about transforming the conditions that shape opportunity and oppression.

Why It Matters

Social justice movements often split when advocates prioritize one quadrant over the rest:

- Some insist on personal growth and self-examination. (UL)

- Others demand systemic reform. (LR)

- Still others focus on changing language and culture. (LL)

- Or call out specific behaviors and actions. (UR)

Each approach is valid. But when one is treated as the only path to justice—and the others as distractions or betrayals—movements fracture, reform efforts stall, and polarization deepens. Quadrant literacy doesn’t dilute the struggle for justice—it deepens it. It lets us recognize:

- That personal awareness without structural change is incomplete.

- That changing language without changing laws isn’t enough.

- That systems without stories lose their soul.

- That action without reflection leads to burnout—or backlash.

Integral justice doesn’t flatten these tensions. It orients them. It reminds us that lasting transformation lives in the integration of all four.

INDIVIDUAL

COLLECTIVE

INTERIOR

EXTERIOR

Felt Identity (Inner Experience)

Felt identity, inner experience, personal meaning This is where a person lives their gender from the inside: How do I experience myself? What pronouns feel congruent? What roles or expressions make me feel whole, safe, or alive? This quadrant includes gender dysphoria, euphoria, self-understanding, internalized shame, and personal meaning-making. Therapy, journaling, and inner work live here. From this view, gender is who I know myself to be.

Embodied Biology (Physical Expression)

Biology, anatomy, hormone levels, behavior This is where sex is defined in terms of chromosomes, genitalia, hormone profiles, and observable behaviors. It includes how someone presents (e.g. dress, gait, voice) and what can be seen or measured. Medical professionals and evolutionary psychologists often work here. From this view, sex is a biological classification—empirical and externally verifiable.

Cultural Interpretations of Gender (Shared Meaning)

Cultural meanings, norms, roles, language This is the shared story of gender—how society defines what it means to be a man, a woman, or nonbinary. It includes rites of passage, beauty standards, expectations, taboos, and the narratives we inherit about masculinity and femininity. From this view, gender is a social and linguistic construction, and healing involves cultural awareness, inclusivity, and rewriting old narratives.

Gendered Systems (Social Structures)

Policies, institutions, laws, structural norms Here we find bathrooms, birth certificates, healthcare access, military codes, sports rules, and anti-discrimination policies. These are the systems and structures that reflect or enforce certain views of gender. From this quadrant, the focus is on equity, systemic access, rights protections, and how social architecture shapes identity expression.

Why It Matters

Where biology meets experience, culture meets system—and the conversation gets tangled. Every quadrant offers part of the truth. And every major gender debate in the culture war stems from people speaking from different quadrants without realizing it.

- A biologist defends empirical sex data (UR).

- A trans person speaks from their lived experience (UL).

- An activist critiques societal norms (LL).

- A policy analyst warns of unintended consequences (LR).

Each is holding a piece of the elephant. Conflict arises not because one is “wrong,” but because each assumes their lens is the whole. Quadrant fluency doesn’t flatten these differences. It honors them — and helps us hold the full conversation. Sex, gender, and identity are not just biology. They’re not just feelings. They’re not just culture, and they’re not just politics. They are all of these — and more.

INDIVIDUAL

COLLECTIVE

INTERIOR

EXTERIOR

Spiritual Experience

Spiritual experience, awakening, intention, devotion This is the inward path: spiritual states of consciousness, contemplative insight, personal surrender, direct experience of God, the Divine, or Ultimate Reality. From this view, spirituality is not about belief or behavior — it’s about direct experience and transformation of consciousness. This is the domain of contemplatives, mystics, and inner devotional practices. Meditation, prayer, and the “eye of spirit” all live here.

Spiritual Practice

Practices, behavior, rituals, neurobiology This quadrant tracks the external expression of spirituality: what people do. That includes rituals, postures, breathwork, dietary rules, even brainwave patterns during meditation. Scientific studies of spirituality, embodied practices, and behavioral disciplines (like keeping the sabbath or performing ablutions) all live here. From this view, spirituality is enacted through visible action.

Shared Beliefs

Myth, meaning, belief systems, shared identity This is the cultural heart of religion: symbols, myths, sacred texts, values, and the deep “we” of belonging. This is where people say, “We are Jewish,” or “Our tradition holds that…” It includes intersubjective meaning-making, group identity, moral frameworks, and inherited narratives. From this view, spirituality is about shared understanding and sacred story.

Religious Institutions

Institutions, traditions, hierarchies, systems This is the structural quadrant of organized religion: churches, mosques, temples, priesthoods, funding structures, publishing arms, laws, and cultural roles. It includes canonization, institutional authority, historical development, and the machinery of preservation and transmission. From this view, religion is a social system—a durable architecture for preserving and sustaining the sacred.

Why It Matters

Where awakening, behavior, community, and cosmology all meet—and sometimes clash. Every spiritual path touches all four quadrants. But every tradition — and every seeker — tends to lean heavily into one or two.

- The mystic pursues direct experience (UL)

- The believer participates in shared meaning (LL)

- The practitioner engages embodied discipline

- The faithful maintain sacred institutions (LR)

Conflicts arise when one quadrant is absolutized.

- The institution protects its structure, but forgets its source

- The mystic dissolves into experience, but disconnects from shared life

- The practitioner perfects their form, but loses the spark

- The believer defends meaning, but forgets the truth

True religion—or mature spirituality—is tetra-enacted. That is, it touches the heart, guides the body, speaks to the tribe, and holds up across generations. The quadrants don’t dissolve the sacred. They reveal its full shape. And they help us walk the path with more humility, depth, and integration.

INDIVIDUAL

COLLECTIVE

INTERIOR

EXTERIOR

Felt Meaning (Signified)

Felt meaning, inner resonance, intentional insight The signified is the inner, subjective meaning as experienced by the individual. It’s the insight behind the metaphor, the emotional charge behind a word, the intuitive sense of what something means. This is the realm of the felt meaning—what the sign points to in lived awareness. From this view, meaning doesn’t reside in the symbol itself, but in what it evokes within.

Symbolic Expression (Signifier)

Words, symbols, sounds, neural correlates The signifier is the physical or behavioral expression—the material mark, sound, or gesture that carries meaning. This includes spoken language, written text, visual symbols, and even brain patterns. It’s what you can point to, record, or analyze. From this lens, meaning is embedded in the form of the sign—the observable vehicle of communication.

Interpretive Context (Semantics)

Shared meaning, interpretive context, cultural resonance Semantics here refers to the shared, intersubjective background that gives signs their meaning. Language, culture, and worldviews shape how signs are interpreted. A word can mean liberation in one group and offense in another. From this view, meaning is socially constructed—it arises between us, not within or outside of us alone.

Structural Constraints (Syntax)

Rules, systems, structures, grammar Syntax refers to the system-level rules and patterns that govern how signifiers can be arranged and used. It’s the domain of grammar, media formats, algorithms, legal language, and all structural conditions that make certain forms of meaning possible or prohibited. From this view, meaning depends on how signs are structurally organized and systemically regulated.

Why It Matters

We often ask: “What does this really mean?” But that question itself splits the elephant.

- Some say it’s about intent (UL – signified)

- Others say it’s in the word itself (UR – signifier)

- Others point to social context (LL – semantics)

- Still others blame or analyze the system (LR – syntax)

Each is right. Each is incomplete. Meaning doesn’t arise in a single place. It emerges when all four of these dimensions come into relation:

- A signifier is expressed

- A signified is felt or intended

- Semantics shape the shared interpretation

- Syntax structures how it can be communicated or constrained

That’s why integral semiotics is so powerful. It doesn’t just explain meaning, it locates it. And when we can locate meaning in all four quadrants, we stop mistaking part of the message for the whole. We begin to communicate—and interpret—with real depth.

INDIVIDUAL

COLLECTIVE

INTERIOR

EXTERIOR

Authenticity (Sincerity & Intention)

Sincerity, intention, self-honesty This is the first-person domain of truthfulness—whether someone is being honest about their own internal state. Are they speaking authentically? Are they in touch with their own motives and emotions? This form of truth is judged by integrity and inner alignment. Practices like shadow work, therapy, and meditation focus here. From this view, truth begins with being real.

Empirical Validity (Objective Fact)

Objective correspondence, observable fact This is the classic “truth-as-fact” quadrant: does the claim match observable reality? Truth here is propositional and third-person: measurable, testable, empirical. This is where science, logic, and rational inquiry live. From this view, truth is a mirror of the world—a map that either matches the territory or doesn’t.

Cultural Resonance (Shared Justness)

Mutual understanding, cultural resonance, shared norms This is truth as intersubjective rightness—does a claim make sense within a shared worldview? Is it ethically sound, culturally appropriate, socially just? This is the quadrant of hermeneutics, ethics, and narrative meaning. From this view, truth is not just about facts—it’s about what feels right to us, together.

Systemic Workability (Functional Fit)

Systemic coherence, utility, survival value This quadrant looks at how well something works within larger systems. It’s not about sincerity (UL), factual accuracy (UR), or shared ethics (LL)—it’s about pragmatic integration. Does this belief, tool, or policy function within its environment? From this view, truth is what’s structurally effective. Systems theory, design thinking, and cybernetics live here.

Why It Matters

We often say “truth” as if it were a single thing. But we’re usually referring to one of four very different standards:

- “That’s not true!” (UR – factual accuracy)

- “That doesn’t feel authentic.” (UL – sincerity)

- “That’s unjust and harmful.” (LL – cultural rightness)

- “That’s not going to work.” (LR – systemic fit)

Each is a valid face of truth. Each comes from a different quadrant. And each has its own blind spots if taken alone. A statement can be factually accurate (UR) but ethically disturbing (LL). A person can be sincere (UL) but misinformed (UR). A system can be efficient (LR) but unjust (LL). Truth breaks when one quadrant tries to dominate the rest. But truth deepens when we honor all four. This integral approach doesn’t flatten truth—it liberates it. It lets science, ethics, introspection, and systems each speak in their own language, while teaching us how to listen for what’s missing.

INDIVIDUAL

COLLECTIVE

INTERIOR

EXTERIOR

Inner Knowing (Direct Insight)

First-person knowledge, introspection, phenomenology This is first-person knowing: immediate experience, intuition, self-awareness, and meaning-making from within. Schools of thought here include phenomenology (Husserl), introspectionism, constructivism, and mystical or contemplative epistemologies. Knowledge here is gained by looking inward—through disciplined introspection or meditative inquiry. It’s tested by coherence with inner insight, resonance, or transformation. “I know because I’ve seen it in myself.”

Observable Knowing (Empirical Observation)

Empiricism, observation, sensory data, scientific method This is third-person, objective knowing: knowledge derived from what can be measured, seen, or quantified. It includes empiricism (Locke, Hume), positivism, behaviorism, and neuroscience-informed cognition. Knowledge is acquired through the senses and verified through repeatable observation. “I know because I measured it, and you can too.”

Cultural Knowing (Intersubjective Meaning)

Hermeneutics, cultural epistemology, social constructionism Here, knowing is intersubjective—arising within shared language, culture, and meaning systems. Truth is shaped by dialogue, worldview, power relations, and interpretive frames. This includes hermeneutics (Gadamer, Ricoeur), postmodernism, feminist epistemology, and social constructionism. Knowing is embedded in culture, and “truth” is what fits our shared horizon. “I know because we agree it makes sense here.”

Systemic Knowing (Functional Coherence)

Systems theory, cybernetics, logic models, information flows This quadrant focuses on functional knowledge: how systems behave, how inputs lead to outputs, how information flows. This includes systems epistemology, cybernetics, computational models, and pragmatic rationalism. Knowledge is validated by functional fit—how well it works across a network or structure. “I know because the system responds predictably, consistently, and efficiently.”

Where knowing arises through experience, observation, culture, and system logic.

Why It Matters

When people debate “what counts as knowledge,” they’re often arguing from different quadrants:

- The empiricist says: “Show me the data.” (UR)

- The mystic says: “I experienced it directly.” (UL)

- The postmodernist says: “Your ‘truth’ is culturally constructed.” (LL)

- The technocrat says: “The model works, end of story.” (LR)

Each is practicing a different kind of epistemology. Each is valid within its quadrant. But when one kind of knowing is elevated as the only valid form, the result is fragmentation, misunderstanding, and epistemological overreach. Integral epistemology doesn’t collapse these views—it locates them. It helps us understand:

- What kind of truth is being claimed

- From what perspective

- And using what method of validation

This is how we move from epistemological warfare to epistemological fluency. It’s not just about what you believe. It’s about learning to see how you know—and how others know differently.

The more we learn to see the quadrants in each field, the less we get stuck in ideological battles and the more we can build bridges between methods, models, and worldviews.

Practical Navigation: How to Use the Quadrants

You don’t need to be a philosopher or theorist to start applying quadrant thinking. You just need to practice asking better questions.

Here are some simple ways to begin:

🧭 The Quadrant Compass

When faced with a problem or decision, pause and ask:

- Upper-Left: What’s going on inside the individuals involved? (Feelings, motivations, stories)

- Upper-Right: What’s happening in their behavior or biology? (Actions, patterns, measurable data)

- Lower-Left: What shared meanings or cultural forces are at play? (Norms, values, group identity)

- Lower-Right: What systems or structures are shaping this? (Institutions, incentives, environments)

You’ll be surprised how often the “solution” lies in a quadrant you hadn’t considered.

🔍 Spotting Quadrant Collisions

When you notice people arguing, ask yourself: Are they actually disagreeing — or are they talking from different quadrants?

- A scientist says, “Depression is a chemical imbalance.” (UR)

- A therapist says, “It’s unresolved trauma.” (UL)

- A sociologist says, “It’s cultural disconnection.” (LL)

- A policy advocate says, “It’s economic precarity.” (LR)

They’re all correct — just incomplete. And seeing that shifts the conversation from “Who’s right?” to “How do these truths fit together?”

What Is Your Native Perspective?

Each of us is born into a world far too vast to grasp all at once — so our minds do something brilliant: they find a home base from which to make sense of it all. This home base is your native perspective — the lens you instinctively reach for when trying to understand yourself, other people, and the world around you.

Integral theory describes four primary perspectives that are always motivating you and shaping every moment of your life: inner experience, action, relationships, and systems:

All four perspectives are always present, like the four cardinal directions on a map. But most of us have one that feels like true north — a familiar orientation we return to again and again. A second one often supports and strengthens it. And one or two may feel like foreign territory — the directions we forget to look, or even resist.

🧘

A Simple Reflection Practice

Before we build a formal quiz, you can begin by simply noticing yourself:

When you’re trying to solve a problem, where does your attention go first — inward to how you feel, outward to what you can do, toward others and their input, or toward the broader system at play?

Which of those four perspectives feels the most natural and trustworthy? Which feels like hard work?

Where in your life have you thrived by leaning into your native perspective — and where might that very strength sometimes become a blind spot?

There’s no “right” answer here. Each perspective is a vital part of the whole. But learning your native orientation is the first step toward a bigger kind of intelligence — one that doesn’t just inhabit a single perspective, but can integrate all four.

Becoming a Bridge

The world is growing more complex, and our old ways of knowing can’t keep up. We’re drowning in information but starving for coherence. We’re surrounded by truths but unable to hold them together.

The four quadrants offer a way forward — not as a final answer, but as a framework for integration. They help us navigate complexity without collapsing it, honor diversity without dissolving it, and hold multiple truths without losing sight of the whole.

And in a fractured world, the people who can do that — who can see whole — are the ones who will lead us forward. They are the translators, the bridge-builders, the connectors between worlds.

This is the beginning of that journey. Because once you learn to see reality through all four windows, you’ll never mistake a single view for the whole again.

And that’s where Integral thinking truly begins.

✅ Next Steps: Explore how these four perspectives play out across the fields that matter most — from psychology and health to politics, art, and spirituality. Each is a laboratory for learning to “see whole.” And each is a doorway into the deeper path of integral practice.

This introduction is just the first step. The more you explore these primordial perspectives — in yourself, your relationships, your work, and the world — the more fluent you become in the grammar of reality itself. And from that fluency, a new kind of wisdom emerges — one capable of holding complexity with compassion, and diversity with depth.

Welcome to the Integral view.

Corey W. deVos is editor and producer of Integral Life. He has worked for Integral Institute/Integal Life since Spring of 2003, and has been a student of integral theory and practice since 1996. Corey is also a professional woodworker, and many of his artworks can be found in his VisionLogix art gallery.

The Four Quadrants

The Four Quadrants

The Four Quadrants Across Multiple Fields of Knowledge

The Four Quadrants Across Multiple Fields of Knowledge